SANTA ANNA’S ALLY through much of their working relationship, Castrillón often took exception to Santa Anna’s decisions during the Texas Revolution. He opposed the hurried assault on the Alamo. Yet when he received his orders to lead the battle's first column of troops, he did so with expert efficiency.

A humane and honorable soldier, Castrillón also pleaded clemency on behalf of the seven Texian fighters who survived the Alamo siege. Castrillón's arguments for mercy were ignored, and the men were executed. Castrillón again stated his protest when Santa Anna ordered the execution of the Goliad prisoners.

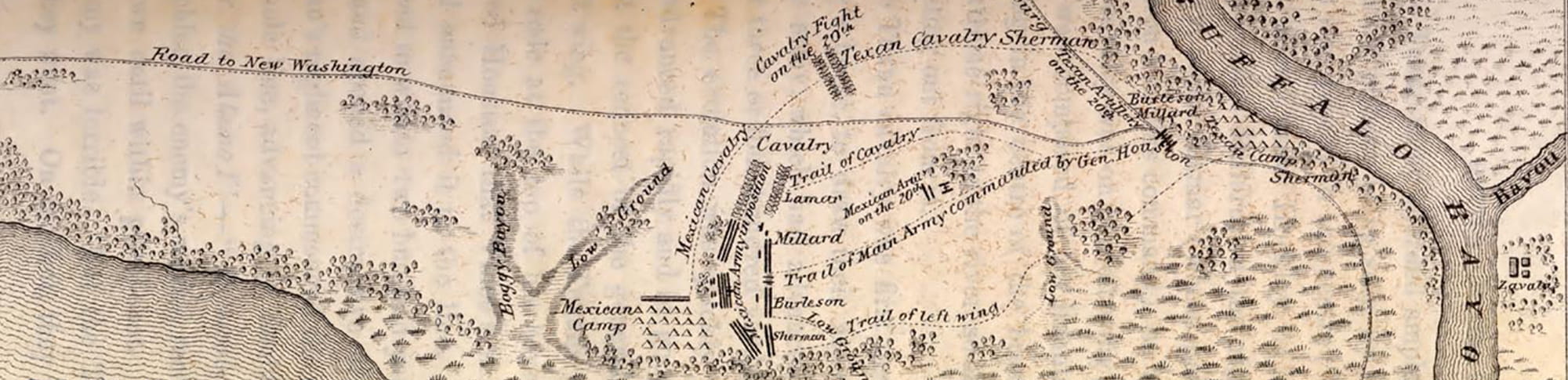

Castrillón's compassion was a sign of kindness, not weakness. When the Texians roused Mexican forces from their afternoon siesta on April 21, 1836, at the Battle of San Jacinto, he was one of the few Mexican officers to stand his ground.

His bravery was recorded in the memoirs of Texian second lieutentant Walter Paye Lane:

“As we charged into them the General commanding the Tampico Battalion (their best troops) tried to rally his men, but could not. He drew himself up, faced us, and said in Spanish: ‘I have been in forty battles and never showed my back; I am too old to do it now.’

He continued: “Gen. Rusk hallooed to his men, ‘Don't shoot him!’ and knocked up some of their guns; but others ran around and riddled him with balls. I was sorry for him. He was an old Castilian gentleman, Gen. Castrillo."

Honored on both sides of the Texas Revolution — except by Santa Anna, who blamed the loss at San Jacinto in part on Castrillón — he was even buried in the family graveyard of Lorenzo de Zavala, the vice-president of Texas.