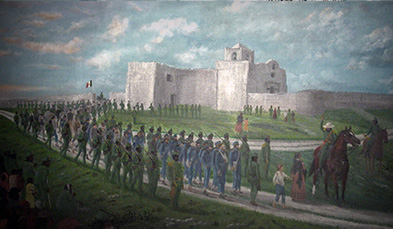

A Dark Time for the Rebellion

IN MARCH OF 1836, things were not going well for the Texian revolutionaries. Having declared independence from the official Mexican government, they were now running from the Mexican army — and running out of time.

General Sam Houston’s men, their families uprooted and futures uncertain, were spoiling for a fight. On April 17th, their eastward retreat led them to a fateful fork in the road. One road led to Louisiana and possible refuge in the United States. The other led to Harrisburg and a showdown with General Santa Anna. The Texian army took the road to Harrisburg without objection from Houston.

The next day, Texian scouts intercepted a Mexican courier carrying letters that revealed that Santa Anna was at New Washington (present-day Morgan's Point), personally leading a vanguard of just 750 men that was separated from the rest of his army. Houston had been hoping for just such an opportunity. If Houston could force a confrontation now, before Santa Anna’s army could bring reinforcements, his Texians just might win the day.

Houston reached White Oak Bayou that same day, where he learned that Santa Anna’s forces had just crossed the nearby bridge over Vince’s Bayou. On the 19th, Houston crossed Buffalo Bayou between Sims’ and Vince’s Bayous just outside of Harrisburg, leaving behind some 257 men who were too ill to fight to guard the baggage train. The army marched on till midnight, until they were too exhausted to continue.

“The army will cross and we will meet the enemy. Some of us may be killed and must be killed; but soldiers remember the Alamo! the Alamo! the Alamo!”

The next morning, April 20th, the Texians continued their forced march down the bayou toward Lynch’s Ferry. Whoever won the race to the ferry would get to choose the ground of the coming battle. The Texians won the race, arriving at the ferry before mid-morning and capturing one of Santa Anna’s supply boats. They then withdrew about a mile and encamped in a wooded area with their backs to Buffalo Bayou. Their left flank was protected from Mexican cavalry by marshland and the San Jacinto River; their front was concealed by a slight rise of ground covered by tall prairie grass. The Texian army numbered just 935 men.