Veteran Bio

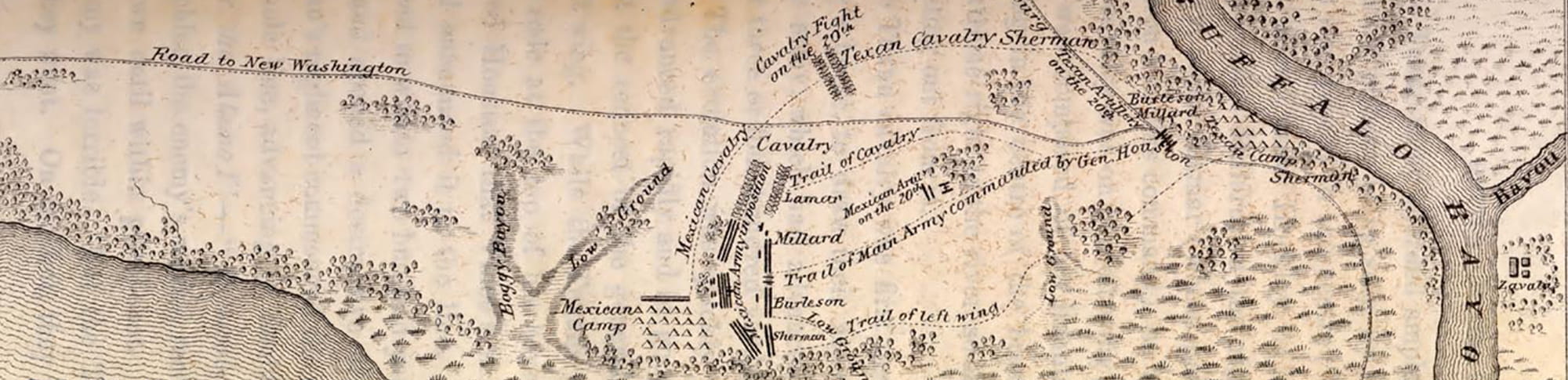

The Kemp Sketch

(What is this?) | Download the original typescript

HORTON, ALEXANDER (Sandy) -- Born in North Carolina April 10, 1810, son of Julius and Susannah (Purnell) Horton. His parents moved to Louisiana early in the year 1818 and there his father died in May of that year, survived by his widow and nine children. Mrs. Horton and family moved to Ayish Bayou (San Augustine), Texas, in January, 1824.

Read The Full Bio

On a winter night in 1826 his mother and sisters and an orphan child eight years old whom Mrs. Horton had adopted were gathered around the firs in the rude log hut, Alexander, or "Sandy," as he was called, being absent, when a party of three Indians entered and demanded possession of the orphan. Mrs. Morton seized a shovel and being a powerful woman, felled the advancing Indian, with an uplifted knife in his hand, to the floor, and a fearful struggle followed. Two of her daughters escaped at this moment and ran through the darkness for "Sandy," who was distant three fourths of a mile. With two other men he hastened home. There stood his mother in one corner worn out with the struggle, blood streaming from her head and face, but still clinging with one hand to the trembling orphan, and holding the shovel in the other. With his rifle barrel Sandy laid one Indian bleeding and senseless upon the floor, while the other savages escaped.

In 1827 when the "Fredonian War" began in East Texas, Mr. Horton had intended to be neutral. Haden Edwards, however, according to Mr. Horton, issued a proclamation in which he warned all of the settlers that if they did not join forces with him, they would be driven out of the county and their property confiscated. Horton and a few of the settlers who had not fled across the Sabine then joined Stephen Prater and about a hundred Indians under him and marched against the Fredonian garrison. The Fredonians surrendered without a show of resistance and the "war" ended.

Next Mr. Horton served under John W. Bullock against the Mexican garrison commanded by Colonel Jose de las Piedras in 1832. In 1835 he was sent as a delegate to the Consultation from San Augustine Municipality. In an unofficial capacity he attended the Constitutional Convention at Washington-on-the-Brazos in 1836. While there he was appointed an aide-de-camp on the staff of General Houston with rank of major. He said that he left Washington with General Houston, George W. Hockley, Richardson Scurry and one other man on March 6th for Gonzales.

On April 9, 1839, Major Horton received Donation Certificate No. 850 for 640 acres of land for having participated in the battle of San Jacinto. In Service Record No. 489 it is certified that he had served in the army from November 18, 1835, to January 30, 1837. He received Bounty Certificate No. 934 December 15, 1837, for his services from November 18, 1835, to September 20, 1836. He received one-fourth of a league of land in de Zavala's colony and on March 22, 1838, was issued a Headright Certificate for three-fourths of a league and one labor of land by the San Augustine County Board of Land Commissioners, of which he was president.

President Houston appointed Major Horton to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel of a regiment of Mounted Gunmen raised for the defense of the frontier, the senate confirming May 31, 1837. In 1838 he was appointed Collector of Customs for the District of San Augustine. During the "war" in East Texas, Colonel Horton was President Houston's messenger to the Regulators and Moderators. He was at one time Mayor of San Augustine and at another a member of the State Legislature from San Augustine County, 15th legislature in 1876.

Colonel Horton was married to Mrs. Elizabeth Lattin, widow of Adolph N. Lattin, on January 23, 1837. To this union were born the following children: San Houston Horton, born December 2, 1837, and died after the year 1891; Eliza Horton, born March 15, 1841, and died July 2, 1853; and Mary Horton, born September 15, 1844, and died December 4, 1844. Mrs. Horton was born at Port Gibson, Mississippi, April 20, 1808, and died at San Augustine, Texas, July 30, 1846.

Colonel Horton was married on December 30, 1847, to Mary Harrell, who was born in Mississippi, and died at San Augustine, Texas, August 29, 1923. Colonel Horton died in 1893, while a member of the Texas Veterans Association. In 1829 a joint monument was erected at the graves of Colonel and Mrs. Horton by the State of Texas.

Children of Colonel Alexander Horton and Mary Harrell Horton were Wade W., who never married; Elizabeth, who married J. H. Sheffield; Susan, who married J. H. McClanahan; Lavina, who married Hal Neal; Emma, who married Tom C. Murphy; Alexander, who never married; and Mary Horton, who married J. W. Richey.

A sketch of Colonel Horton's life, written by himself October 18, 1891, was published in Volume 14 of the Quarterly of the Texas Historical Association.

Col. Alexander Horton. Died at his residence near the town of San Augustine, Texas, January 11, 1894. He was born in Halifax County North Carolina, April 18, 1810. His father's name was Julius Horton and his mother's name was Susannah Purnell. His father moved to the State of Louisiana in 1818 and there died in the month of May, 1818, laving the mother of Col. Horton a widow with nine helpless children. His mother moved to San Augustine, Texas, in 1824, finding the colony almost uninhabited. He came without father, money or friends. At one time all the citizens of the County left and fled to the United States except Edward Teel and A. Horton. The County was again abandoned, but Col. Horton was then in the army acting aide d' camp to General Houston.

He was with Texas from 1824 up to the time of his death. He served in all her wars, beginning with the Freedonian war, 1827; in the war between Santa Anna and Bustimento, 1832; in the war of 1835 and 36; Santa Anna and the Republic of Texas, and in the war of 1839; against the Cherokees. He was sheriff of San Augustine 4 years, and was president of the Board of Land Commissioners in 1838. Custom House collector, 1839; was mayor of San Augustine. He was a member of the consultation in 1835, served one term in the Legislature. There never was a call from Texas for help in the hour of danger, without his being there to render all of the assistance in his power.

North Carolina has always been proud of the valor of her sons, though that valor be displayed upon the soil of distant lands.

Will not North Carolinians in Texas rise up and do honor to the name of the sleeping hero? And will not all citizens of Texas, who are enjoying the liberty and prosperity, for which he struggled so hard and so bravely, unite in erecting a monument to his memory worthy of his name.

His second wife was Mary E Harrell. Born in Mississippi September 6, 1836; married to Alexander Horton December 30, 1847; died August 29, 1923.

Horton's sister married Col. James W. Bullock.

No. 501 for 320 acres, Jan. 30, 1849

Duration of war.

HORTON, ALEXANDER -- The following was written by Colonel Horton at San Augustine, Texas, October 18, 1891:

"I was born in the State of North Carolina 18th day of April, 1810. My father's name was Julius Horton, my mother's name was Susannah Purnell. My father moved to the State of Louisiana in 1818. He died in the month of May, 1818, leaving my mother with nine helpless children, Nancy, Elizabeth, Sarah, Samuel, Sandy or Alexander, Martha, Wade, Henry, Susan. My mother moved to Texas first part of January 1824 and settled in San Augustine then called Ayish Bayou; found the country almost uninhabited. There were but few people then living in the county. I found James Gaines keeping a ferry on the Sabine river. The next house was Maximilian's. At the Polygoch, Macon C. Cole. The next settler, Brian Doughtery, living at the place where Elisha Roberts formerly lived. The next place was Nathan Davis living at the crossing of the Ayish Bayou. The next place occupied was where William Blount now resides, but the houses were east of the houses where Mr. Blount now resides. At that place lived John A. Williams. From there there was no one living, until you came to the place where Milton Garret lived. There, a man named Fulcher lived, and at or near the Attoyac lived Thomas Spencer. That was about the number of inhabitants living in this county first Jany. 1824. But the county from this date began to make rapid improvements and all things seemed prosperous. Among the early settles of this county were some of the noblest men to be found in any county. They (were) generous, kind, honest and brave I will here give the names of many of them. I will begin with David and Isaac Renfro, Elisha Roberts, Donald McConald, John Cartwright, Willis Murphy, Phillip A. Sublett, John Chumly, Nathan David, Obadiah Hendrick, John Bodine, John Lout, Bailey Anderson, Benjamin Thomas, Wiley Thomas, Shedrack Thomas, Thomas Cartwright, Isaac Lindsey, John G. Love, Martha Lewis and family, George Jones, Achilles Johnson, Elias K. David, Theodore Dorset, John Dorset, Benjamin Lindsey, Stephen Prater, Wyatt Hanks, James and Horatio Hanks, Solomon Miller, Hiram Brown, William Lace (Lacey), George Tell, Edward Tell, John Sprowl, James Bridges, Ross Bridges, Peter Galloway, John McGinnis. These were the most earliest settlers of East Texas. In 1825 the people began to make rapid improvement, opening large farms and building cotton gins. This year Elisha Roberts, John A. Williams and John Sprowl each erected cotton gins on the main road for at that time there was no one living either north or south of the old King's Highway. In the year 1824 William Quirk built a mill on the Ayish Bayou just above where Hanks Mill now stands. All things went on harmonious for several years, the country filling up rapidly. The first trouble we had commenced 1827. This was what was called the Fredonian war. This grew out of a quarrel between the Mexican citizens of Nacogdoches and Col. Hayden Edwards. Col. Edwards had obtained from the Mexican Government the right to colonize the country south of the road leading from Nacogdoches to the Sabine river, and had settled in the town of Nacogdoches with his family, but a dispute soon arose between him and the Mexican citizens in regard to their land matters. These things were referred to the Mexican authorities who at once decided in favor of the Mexican citizens, and at once took from Edwards his colonial grant and gave the colony to Antonio de Zavalla. This act aroused Edwards to desperation and he at once proceeded to the United States and raised a large force of volunteers, marched upon Nacogdoches and after a short engagement took the town, killing one Mexican and wounding several. They then raised what they called the Fredonian flag, and established the Fredonian Government. He then called upon the citizens of Ayish, Sabine, and Tenaha or Sheby to join. This they refused to do, not seeing any cause for a war with Mexico. This again roused Edwards to desperation and he at once issued a proclamation, giving the citizens a given time to join him, stating that all that did not join by a given time was to be driven out of the country, and their property was to be confiscated. In furtherance of this he set down to this county about 100 men stationed on road about two miles east of the Ayish Bayou. This threat backed by such forced entirely broke up the county. Every citizen of this county except Edward Tell and myself fled across the Sabine. It did seem as if all was lost but at last the comforter came. The evening before the Fredonians were to carry out their threat to my great joy and surprise who should ride up to my mother's but my old and well tried friend Stephen Prater. A braver nor no honester man ever lived in any county. He had with him about 75 or 100 Indian warriors all painted and ready to execute any order given them by Prater. When he rode up to my mother's house he called to me and said: "Not run away yet?" I told him I had not left nor did not intend to leave. He then said: "Are you willing to join us and fight for your country?" I told him I was. Then said he "Saddle your horse and follow me, for I intend to take that Fredonian garrison in the morning or die in the attempt." I at once saddled my horse, shouldered my rifle and fell into line. Stephen Prater had only eight white men with him. The rest of the citizens had gone over Sabine for protection from the government of the United States. I well remember all of them he had with him. James Bridges Sr., James Bridges Jr., Ross Bridges, Peter Calloway and John McGinnis, his two sons Stephen and Freeman, and A. Horton. He marched that evening up in about 400 yards of the Fredonian fort, dismounted his man and at daylight in the morning marched them up near these fortifications, and after telling them the place would be taken by storm, but not to fire or kill any one without we were fired on, the order was given for a charge. When the word was given to charge the Indians raised a war whoop and it was terrible. The Fredonians threw down their arms and begged for quarters which was granted at once. They were all disarmed and put under guard. As next day was the day the troops was to come down to carry out their threat of confiscation, as fast as they arrived they were arrested and put under guard. So in the course of a few hours we had them all under guard. When the news reached Nacogdoches Col. Edwards and the balance of the party fled to the United States, crossing the Sabine river at Richard Haley Crossing in Shelby County: and this was the last of the Fredonian war. This is a true and correct statement; Tho many things may have been left or forgotten what is states is true and correct.

All things after this went on smoothly. The Mexican Government was highly pleased with the part taken by the Americans and at once appointed officers to extend land titles to the colonists, the country rapidly filling up with settlers.

In 1832 a civil war broke out in Mexico, President Bustamente declaring a favor of a monarchial form of government, and General Santa Anna in favor of the Constitution of 1824. The Americans everywhere in Texas took up arms in favor of Santa Anna. At that time there was a regiment of Mexican soldiers stationed at Nacogdoches under the command of Col. Piedras, who declared in favor of the central government. The people of Eastern Texas declared in favor of the Constitution of 1824. The people at once flew to arms and elected John W. Bullock commander in chief. James W. Bullock was a well tried soldier, had served under the immortal Jackson in Indian wars and was with him at the battle of New Orleans. The Texans marched from the town of Nacogdoches the last of July 1832 and on the second day of August formed themselves in regular order of battle and demanded the surrender of the place or the raising of the Santa Anna flag, both of which Col. Piedras refused to do, sending word that he was well prepared and ready to receive us. About ten o'clock on the 2nd day of August the battle began, the Mexicans meeting us at the entrance of the town. A furious fight commenced which lasted all day, the Americans driving them from house to house until they reached the stone house. There they made a desperate stand but was again driven from there to the main fortification, which they called the quartell. This ended the fighting of the 2nd of August. August 3d the Americans was well prepared to commence the fight but to their surprise they found that the Mexicans had that night abandoned the town and had retreated to the west. A call at once was made for volunteers to follow them. 17 men at once volunteered to go after them; attacked them at the crossing of the Angelina, and after a considerable fight in which the Mexicans lost their great cavalry officer Muscus (Musquiz), who was killed in the fight, the Mexicans took possession of John Durst's houses. The Americans then withdrew and took a strong position on the road west of the river, intending to ambuscade and fight the Mexicans to the Brazos, but after waiting until late in the day returned to see what the Mexicans was doing. To our surprise on arriving near the house we saw a white flag floating from Durst's chimney. We approached the place with caution for we had only seventeen men and Piedras had an entire regiment. But we approached as near as we thought prudent and Piedras had his officers come out and surrender themselves prisoners of war. We then was at a loss to know what to do with so many prisoners so we hit upon the following plan: so it was agreed upon that Col. Piedras and his officers should be taken back to Nacogdoches, and that the soldiers should remain where they were until further orders. On arriving at Nacogdoches with our prisoners a treaty was made by way of New Orleans pledging himself not to take up army any more during the war unless fairly exchanged; and this was the end of the war of 1832. The names of the seventeen men I have forgot some of them but remember some of them. I will begin with James Carter, Hiram Brown, John Noilin, William Lloyd, Jack Thompson, George Lewis, Horatio Hanks, James Bradshaw, A. Horton, George Jones; the other names I have forgotten.

When I arrived in Texas in 1824 I found (it) so sparsely settled that there was no regulations in any legal form. As we had no knowledge of the Mexican laws we were a law unto ourselves. But as the country became more thickly settled it became manifest that there must be some rule to collect debts and punish crimes. The people agreed to elect a man whom they called an Alcalde and a Sheriff to execute his orders. The Alcalde's power extended to all cases civil and criminal without any regard to the amount in controversy. Murder, thefts, and all other cases came under his jurisdiction except divorces, and as the old Texas men and women were always true and loyal to each other, divorce cases was never heard of. The Alcalde had the power in all cases to call to his assistance twelve good and lawful citizens to his aid when he deemed it necessary or the parties required it, and the decision of the Alcalde and 12 men was final from which no appeal could be taken, and there was as much justice done then as there is now and not half so much grumbling. The first Alcalde was Baily Anderson, the next was John Sprowl. In 1830 Jacob Garrett was Alcalde, 1831 Elisha Roberts, 1832 Benjamin Lindsey, 1833 William McFarland, in 1834 Charles Taylor was Alcalde. I served as Sheriff under Roberts, Lindsey, McFarland and Taylor, but the year of thirty five called me to the tented field in defense of my country.

The year 1835 brought about a new order of things. After the people had fought for Santa Anna in 1832, looking on his as the Washington of the day, (in) 1835 he turns traitor to the republican party and declared himself Dictator or Emperor. He soon overrun all the Mexican states except Texas, who true to the principles of 1776 refused to submit to his tyrannical form of government, and this brought on the war with Mexico. The people held political meetings everywhere in Texas and resolved to resist the tyrant at all hazards. A consultation was called to meet at San Felipe de Austin to determine what was best. In the mean time the people of Texas had flew to arms; had taken Goliad and San Antonio, and driven the Mexicans out of Texas. When the Consultation met they at once closed the land office in Texas, suspended the laws in all civil cases, and elected Sam Houston Commander in chief of the armies of Texas. Houston repaired to the army but Travis and Fannin refused to give up the command to Houston. He returned home much mortified and the disobedience of orders let to all the great desertion of our armies. Had Fannin and Travis have turned over the command to Houston that fine army would have been saved, but Houston had to return and wait until the meeting of the Convention in Mar. 1836 before he could get the command, and it was too late. On the assembling of the Convention among the earliest acts was to elect Houston Commander in chief, for at that time Travis's letters were coming every day calling for troops, saying that the Mexican army was advancing rapidly on him in great force, but he would hold the post till the last and would never surrender. Houston arrived at Gonzales about 11th of March with only four men: Col. Hockly, Richardson Scurry, A. Horton and one other man. When he reached Gonzales he found the glorious Edward Burleson there with about 400 four hundred men, who had started to reinforce Travis, but on reaching there found that Santa Anna with a powerful army had got there before him and surrounded the Alamo with a force estimated at from 8000 to 10000 thousand men. On Houston's arrival Edward Burleson at once turned over the command to him, and was at once was elected colonel of the first regiment. The great anxiety was the fort of the Alamo. The spies came in that morning (and) said that San Antonio was surrounded by a powerful force so they could not approach near enough to see what was the fate of it, but greatly feared that the town had fallen as all firing had ceased. Soon after Mrs. Dickerson arrived with her infant daughter and that every one had been killed except herself and child and the negro man, that Santa Anna with his whole army was not five miles off for she left them at dinner and had come with a proclamation from Santa Anna offering a pardon to all that would lay down arms and submit to the government, but certain death to all that was found under arms. This proclamation Houston read to the men and then stamped it under his feet and shouted 'Death to Santa Anna, and down with despotism.' All the men joined in the shout. But there was not time to be lost as the enemy was at the door. After a Council of war it was decided that the troops must fall back at once. Orders was given for the women and children to retreat as fast as possible assuring them that troops would cover their retreat and defend them as long as a man was left alive. The retreat was commenced about midnight, the troops following them. Houston retreated to the Colorado, sending word to Fannin to blow up Goliad and join him there, but he refused to do so and paid no regard to Houston's order. Houston remained there many days expecting that Fannin would come to his assistance, but that he failed or refused to do. While waiting there Houston's army was stronger than it ever was afterwards. While waiting for Fannin and expecting him every house, to his great surprise, Carl, a man will skilled in the Mexican affairs, came to camp and brought the dreadful news that Fannin's army had been captured and all killed after their surrender. This dreadful news again had caused great confusion in the army. The army was again obliged to fall back and a large number of our men had to be paroled to take care of their families, and this again greatly reduced our forces. Houston retreated to the Brazos to San Felipe. There he turned up the river on the west side and encamped opposite Groce's Retreat between the river and a large lake, where he remained many days sending out his spies in every direction watching the enemies motions. At last the glorious spy, Henry W. Karnes, brought the news that Santa Anna had forced the crossing of the Brazos at Fort Bend and was marching on to Harrisburg. Houston at once, by the assistance of the steamboat 'Yellowstone,' that was lying at Groce's, threw his army across the Brazos and took up the line of march to Harrisburg, that ended in the defeat of the Mexican army and the securing of the independence of Texas.

In those dark days all seemed to be lost as that little army was all the hopes of Texas, for if that little army had been defeated all was lost, for the Indians were on the point of joining the Mexicans, for on my way home after the battle I passed many Indians about the Trinity painted and armed awaiting the result of the battle, for if that little Texian army had been defeated the Indians would have joined the Mexican army and would have commenced butchering our helpless women and children. When all seemed to be lost the noble Sydney A. Sherman came to our assistance with a glorious Kentucky regiment and rendered great and timely aid and having gloriously led our left wing in the glorious battle of San Jacinto. That battle secured the independence of Texas and laid the foundation of extending the jurisdiction of the United States to the Pacific Ocean.

I was a member of the Consultation (of) 1835, voted for the Declaration of Independence at that time and if it had have carried Texas would have been in a much better condition to have met the enemy than she was in 1836. It would have given us more time to have organized armies, and been much better prepared to have met the enemy. I have been in Texas since 1824, served in all the wars, beginning with Fredonian war 1827, in the war between Santa Anna and Bustamente, 1832, in the war 1835 and 36 between Santa Anna and the Republic of Texas, and in 1839 (war) against the Cherokees under John Boles the great war chief. I have served Texas in various wars. I was first Sheriff for I was President of the Board of Land Commissioners in 1838, Custom House Collector 1839, was Mayor of San Augustine. I was a member of the Consultation in 1835, served you one term in the legislature, and there has never been a call for help in the hour of danger that I was not there I have seen San Augustine twice broken up and abandoned, first in the Fredonian War in 1827 all the citizens of the county left and fled to the United (States) Except Edward Tell and myself. (In) 1836 it was again abandoned but I did not witness that scene for I was in the army acting as Aid-de-camp to General Houston. I have never abandoned my country though I have had to encounter many dangers having come to Texas when only 14 years old without father money or friends, and never received but a very limited education, in fact what I in a great measure acquired by my own exertions with a little assistance from my friends. I an proud to be able to say in truth that I have been always an honest man. At 27 years I married to Elizabeth Latten formerly Elizabeth Cooper by whom I had three children one son and two daughters. My oldest son I named Sam Houston Horton after my glorious old chief that led me to battle, and who remained my best friend through life. Houston Horton is still living. I had also two daughters Eliza and Mary, both dead. I lived with my wife ten years. In the meantime I had by honest esertions accumulated a small fortune but the civil wars of my country left me in my old age penniless poor, having given away a fortune in valuable land for negro property which was taken away from me by the self righteous people of the North, these hypocritical people having dealt in slaves as long as it was profitable in the North and finding out that the money that they had invested in negro property could be better and more profitably invested in factories at once brought their negroes down south and sold them for from one thousand to fifteen hundred dollars to their southern neighbors."

HORTON, ALEXANDER -- THE INCIDENTS BELOW WERE WRITTEN BY S. D. BEWLEY, ONE OF HIS TRUEST FRIENDS

In the county of San Augustine resided in 1826 Mrs. Susan Horton a widow with a grown son, two minor daughters and an orphan child, whom through her great sympathy and noble philanthropy she had picked up as a waif, without parents or protection, and had kindly cared for.

It was on a dark night while she with her little daughters and the orphan were gathered around the firs of the rude log hut, her son being absent, that a party of stalwart Indians pushed open the door and entered into the little family group and peremptorily demanded the orphan of Mrs. Horton, accompanying the demand with an exhibition of their knives hatchets and guns. The orphan, who was then old enough to comprehend the matter, clung with screams to his foster mother, imploring her protection, against the murderous fiends, with a voice that rung out upon the darkness "like the wail above the dead." That noble woman whose name ought to go down through history with the names of Molly Pitcher, Mrs. Dare, and other heroines of America, pressed the child close to her and firmly refused to give it up to the enemy. A scowling look from the foremost Indian, and an uplifted knife in hand that dazzled with a fearful gleam by the firelight upon the hearth, told her plainly that she must yield up the child -- perhaps to be murdered by torture she knew not what -- or her life must pay the forfeit. She seized the shovel and being a powerful woman, felled the advancing Indian to the floor, covering herself and child with his blood, and a fearful struggle between herself and the Indians followed. Her two little daughters escaped at this moment and ran through the darkness for their brother, who was distant three fourths of a mile, and told him the Indians had murdered their mother. In a moment he jerked up an empty rifle, -- the only weapon he could get -- and with two other men plunged through the darkness toward the bloody scene. As they neared the house the yells of the savages, the heavy thuds upon the floor and the crash of chairs and tables made night hideous and his two friends retreated but he fired by that love for a mother that is only felt by the true and the brave, pressed onward to the rescue of his mother if yet alive, or avenge her death if she had already fallen, or die himself in the effort. As he neared the door of his home the darkness was lit up by the fire locke of the Indians on the outside, who, it seems, expected him, but whose flint lock rifles failed to fire. He dashed into the house; there stood his mother in one corner worn but with the struggle the blood streaming from her head and face, and her torn and tattered clothing literally saturated with the gore of the demons but still clinging with one hand to the trembling orphan, and holding in the other a bludgeon, and looking the personification of the noblest Roman or Spartan matrons. Just as her son entered the house in which there were still two Indians, he heard one of them tell her (in English) that he would shut the door and then kill her. Quick as thought a herculean blow with the rifle barrel laid the Indian bleeding and senseless upon the floor, while his blood covered mother was exclaiming, "Thank God, my son has come, Sandy has come." He smote the other Indian a lick that sent him out at the door. At this juncture one of the men who had deserted young Horton come up, when the Indians outside snapped at him but failed to fire. The savages having been thus foiled, the guns failing them, and perhaps expecting that young Horton would soon be reinforced, skulked off in the darkness -- all except the one who said he would kill Mrs. Horton -- he was carried away -- and thus the child and Mrs. Horton were saved from death. That woman was the mother of Col. Alexander Horton now in the Legislature from San Augustine.

A brief reminiscence of Col. Horton may not be amiss in this place. He settled in this country in 1824; was its sheriff from 1831 to 1834; was in the battle of Nacogdoches on the 2nd day of August, 1832; followed the retreating imperialists to the Angelina river where with only sixteen others captured by strategy the entire force of about four hundred men; was representative from this county in the consultation held in 1835 at San Felipe; Accompanied Sam Houston and Col. Forbes in the same year into the Indian Nation, and aided in making a treaty with the Cherokees; joined the Texas Army as Houston's Aide-de-camp at Gonzales; acted in that capacity until after the battle of San Jacinto; and saw Sylvester and nobody but Sylvester bring Santa Anna into camp.

Close

Written by Louis W. Kemp, between 1930 and 1952. Please note that typographical and factual errors have not been corrected from the original sketches. The biographies have been scanned from the original typescripts, a process that sometimes allows for mistakes in the new text. Researchers should verify the accuracy of the texts' contents through other sources before quoting in publications. Additional information on the veteran may be available in the Herzstein Library.

Gallery

of

Battle Statistics

- Died in Battle: No

- Rank: Major

- Company: Aide-de-camp, Commander-in-Chief's staff

Personal Statistics

- Alternate Names: Sandy

- Date of Birth: 1810 Apr 18

- Birthplace: North Carolina, Halifax County

- Origin: Louisiana

- Came to Texas: 1824 Jan

- Date of Death: 1893? 1894 Jan 11

- Comments: Fredonian Rebellion

- Bounty Certificate: 934

- Donation Certificate: 850

- Wife: 1. Elizabeth Lattin; 2. Mary E. Harrell

- Children: Sam Houston Horton; Eliza Horton; Mary Horton; Wade W. Horton; Elizabeth Horton Sheffield; Susan Horton McClanahan; Lavina Horton Neal; Emma Horton Murphy; Alexander Horton; Mary Horton Richey

Additional Resources

Related Artifacts

of